What's in a (cat) Name

Framed Data sets up hack nights where friends can visit, check out the office, and hack on small personal projects. It’s been awhile since I have worked on one myself, so decidedly, I hacked on cats. And who doesn’t like cats?

(For the record, I really don’t like cats. I just like using them in presentations.)

Data to start with

I dug through a few different websites using Google search, ultimately landing on Petfinder for data collection. I liked the web view’s search process, which made it relatively easy to find the JSON they send through the server. The data scraper I built used ehutzelman’s petfinder Ruby gem, and it polled Petfinder for a week until the project had a decently sized data set–roughly 38,000 unique cats.

As features, I exposed what I could through the API: db id (to ensure uniqueness), name, gender, breeds, and size.

Data munging (or “what I learned about cats”)

As always, it’s expected that the majority of work on any data problem is cleanup. Here, that meant learning about what different cat breeds exist, in order to best understand trends in breed and name origin. While some basics were involved (refining all text to lowercase, for example), there certainly required more brute work to produce a clean data set.

What I ultimately learned: most people don’t actually know cat breeds.

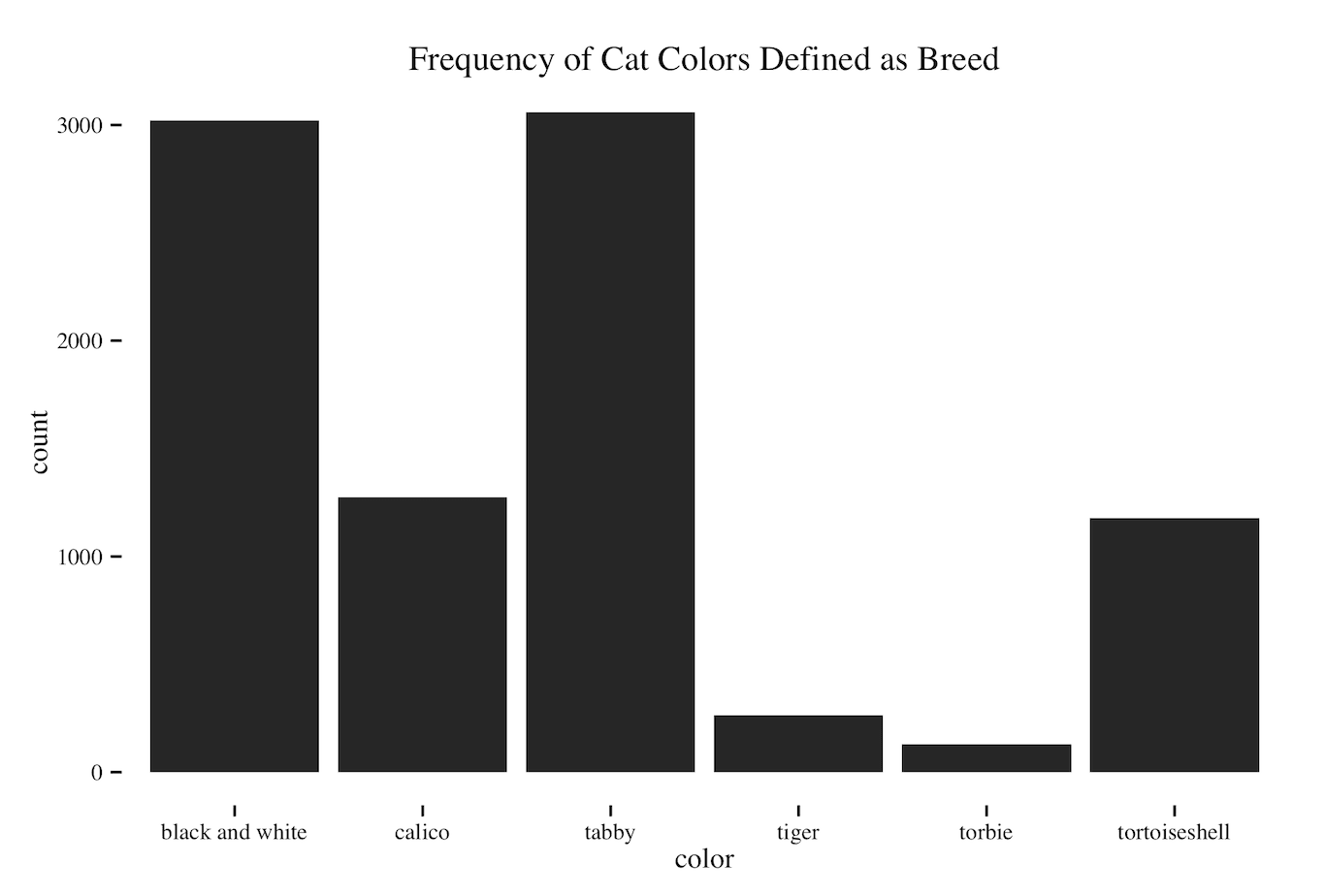

Once I had a unique list of cat breeds, it was time to investigate what each breed looked like. I often found that many of the cat breeds listed were not breeds at all. Cat “breeds” like calico, tortoiseshell, tabby, and tortie actually explained the pattern and color of the cat’s hair, but were different from the actual breeds, such as Manx, Javanese, Ragdoll, or Chartreux.

While some of these cats had secondary breeds that consisted of the real breed, many were still missing. Just shy of 9000 cats (23% of the dataset) could no longer be identified by a breed.

Finally, I removed name outliers. Since I was mostly interested in how people name cats, I used plyr’s ddply to count cat name frequency and removed names that occurred infrequently, leaving 14 names.

Data findings

To no surprise, if many do not know what their cat’s breed is, then it was less likely to expect any correlation in naming. Instead, turning to the cat’s color and size, I found some obvious but neat determiners of what a cat’s name will be.

Cat color

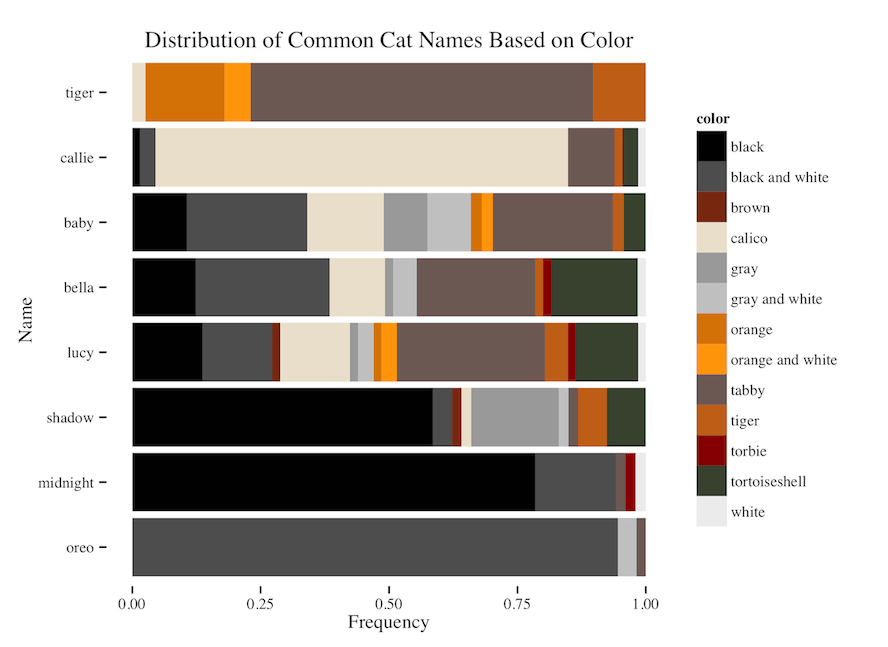

A cat’s color can be very indicative for certain names. Calico cats tend to be named Callie, black and white cats often named Oreo, and black cats hover between Midnight and Shadow. Below, I called to attention some clear preferences to names based on color, where Baby, Bella, and Lucy show what the typical color distribution looked like.

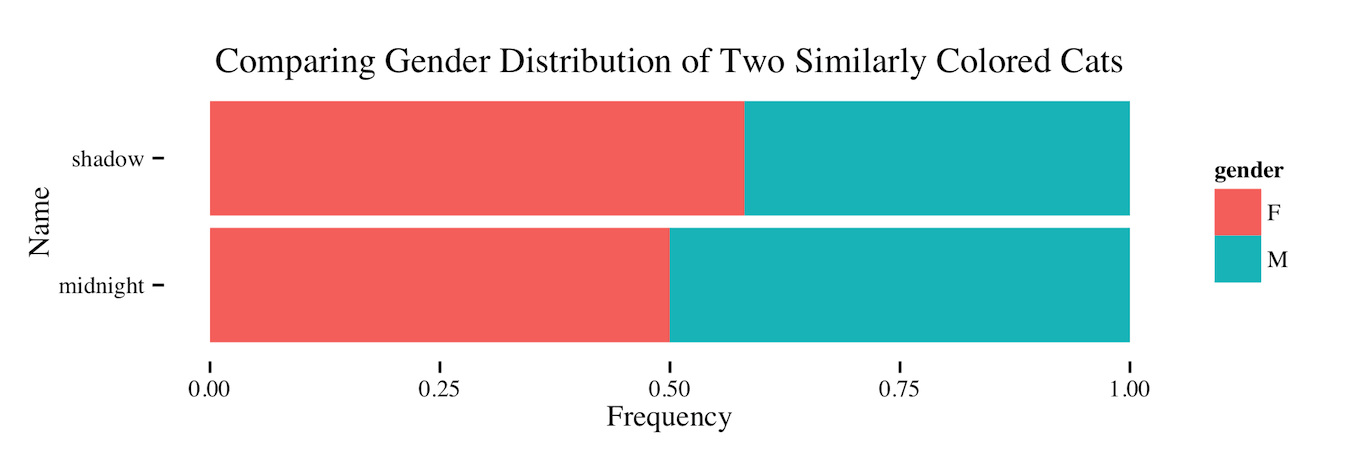

Although Midnight (79 cats) and Shadow (89) seem like gender ambiguous names, checking distribution based on gender suggested otherwise:

Cat size

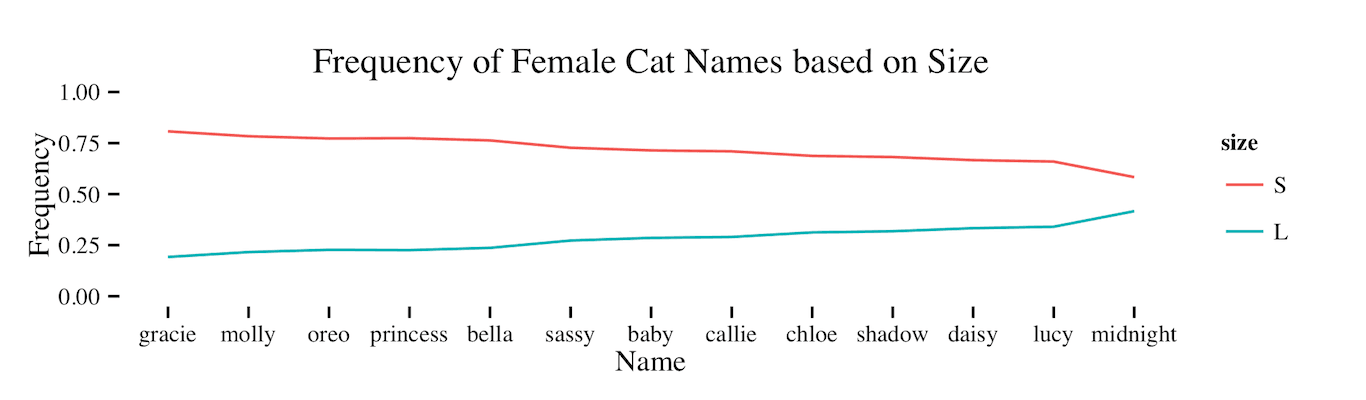

There also displayed light correlations with a cat’s size and its name. Here, I considered only female cats. Females represented the majority of the data, and this split also removed the likelihood that the cat was larger because it was male. I also filtered down to two distinct sizes: small and large. I removed medium since it’s not clear how a cat would be labeled medium versus small or large, and I also removed extra large since it had a small sample size.

The data seems to suggest some names are more common with small female cats than large female cats, Gracie and Molly being exceptionally small cats, compared to Midnight, which was almost twice as often a large cat. Why? Who knows. Cats make me sneeze.

Next Steps

Interestingly enough, the most common cat name ended up being Bella, though my bet, there’s some outside influence.

Although I completely avoided working with the text descriptions of each cat, I imagine by processing the description text, more details can be extracted that aren’t captured in the breed, color, and size. Next time!